In order to understand how Pipelines conceptualizes the city of Edmonton, we need to acknowledge four theoretical underpinnings that have intricate and not uncontentious relations to each other.

First, Pipelines wants to make it clear that the city is a place. The distinction between space and place has traditionally rested on the individual, subjective experience of the city. Space is a set of coordinates, an area delineated by objectivity alone, whereas place is what happens when this area is experienced by someone who creates memories, who builds his or her own path along with the traces left behind, who questions the layers of meaning and experience in any given location.[1] Space is the Google map on your smartphone; place is the creative cartography of a project like hitotoki, which impregnates that Google map with short, place-specific narratives.[2]

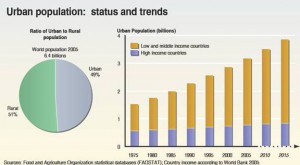

Second, and working at cross purposes to the concept of city as place, we are living less and less inside a city, and more and more inside urbanization itself. That is: inside a material and social space increasingly perceived to be in a constant state of flux, and in regards to which the stakes brought forth by material development — expansion, superposition, destruction, reconstruction — are

Second, and working at cross purposes to the concept of city as place, we are living less and less inside a city, and more and more inside urbanization itself. That is: inside a material and social space increasingly perceived to be in a constant state of flux, and in regards to which the stakes brought forth by material development — expansion, superposition, destruction, reconstruction — are  challenging the formerly strict structural distinctions between centrality and periphery.[3] The reshaping and acceleration of urban life at the onset of the new century brings a renewed context in which to think the production of knowledge itself, since the urbanization’s native tongue is not geography but data: demographics, square footage, corporate holdings, housing values. The notions of flux and circulation endemic to such data permeate all this and infect our conception of the urban fabric itself.[4]

challenging the formerly strict structural distinctions between centrality and periphery.[3] The reshaping and acceleration of urban life at the onset of the new century brings a renewed context in which to think the production of knowledge itself, since the urbanization’s native tongue is not geography but data: demographics, square footage, corporate holdings, housing values. The notions of flux and circulation endemic to such data permeate all this and infect our conception of the urban fabric itself.[4]

Third: we are not content with simply walking, commuting or driving in our cities anymore. Many of us are now reflecting on how we accomplish these things while we accomplish them on mobile digital devices and GPS-enabled maps.  The space between the digital and the urban is shrinking toward the surface where subjectivity and urban space intersect, the screen on which we are becoming our own characters in a new type of urban narrative. This urban reality is less “virtual” or disincarnated than it appeared to be even a decade ago. Pipelines holds that there is a new creativity in the redoubling of one’s experience on the screen of a mobile device, even while our belief in the classical, linear, bildungsroman-type narrative is challenged by these unforeseen digital parameters. The mobility of the screen itself has become as important as the one found in images. Not only is the representation of urban experience being transformed by technology, but so is the way we look at ourselves through the city.

The space between the digital and the urban is shrinking toward the surface where subjectivity and urban space intersect, the screen on which we are becoming our own characters in a new type of urban narrative. This urban reality is less “virtual” or disincarnated than it appeared to be even a decade ago. Pipelines holds that there is a new creativity in the redoubling of one’s experience on the screen of a mobile device, even while our belief in the classical, linear, bildungsroman-type narrative is challenged by these unforeseen digital parameters. The mobility of the screen itself has become as important as the one found in images. Not only is the representation of urban experience being transformed by technology, but so is the way we look at ourselves through the city.

Fourth, it appears to us that the lesser-known Canadian cities have recently become fascinating. Entire neighborhoods spring up from the ground in a matter of weeks; large downtown areas are re-conceived and re-branded through ambitious projects. This is a spectacle that Canadian cities like Edmonton have been infamous for in the past decade or so. And  this is a rare experience in the history of urban development. From the perspective of the everyday, individual life, it might very well be an untold experience. As a post-war, car-centered, mid-sized city, Edmonton represents both a unique and representative case study. Edmonton is unique in that it is North America’s most northern city of over one million inhabitants but it is also representative of the main type of urban space developed after World War II and based on mobility. These are cities that have been either understudied or dismissed as characterless manifestations of “sprawl.” It is precisely this lack that animates this project. Edmonton is under-narrated even by comparison to cities of similar age and type.[5] However, far from being a detriment to this project, being under-storied is a positive boon, since it means Edmonton cityspace is still malleable, amenable to a plethora of stories that intersect in complex ways. Any single city location might mean a number of things, and our various pipelines attempt to distribute distinct meanings through semiotically dense urban spaces.

this is a rare experience in the history of urban development. From the perspective of the everyday, individual life, it might very well be an untold experience. As a post-war, car-centered, mid-sized city, Edmonton represents both a unique and representative case study. Edmonton is unique in that it is North America’s most northern city of over one million inhabitants but it is also representative of the main type of urban space developed after World War II and based on mobility. These are cities that have been either understudied or dismissed as characterless manifestations of “sprawl.” It is precisely this lack that animates this project. Edmonton is under-narrated even by comparison to cities of similar age and type.[5] However, far from being a detriment to this project, being under-storied is a positive boon, since it means Edmonton cityspace is still malleable, amenable to a plethora of stories that intersect in complex ways. Any single city location might mean a number of things, and our various pipelines attempt to distribute distinct meanings through semiotically dense urban spaces.

These four contentiously connected convictions demonstrate the need for new urban narratives – and, in fact, new narrative forms. With Pipelines, we certainly believe the city should be defined from the ground up. But the combination of self-reflexive digital mediations, the rapid and disorienting pace of urbanization, the ubiquity of data and the increasing typicality of urban forms (even walkable European cities are being transformed by housing tracts and big box stores) urges us to ask new questions about a city like Edmonton today. How can we narrate the personal experience of living inside urbanization? What do individual narratives absorb from their physical urban surroundings? What happens to these individual narratives when they get access to urban data showing how their physical surroundings are themselves the result of complex histories yet to be told? What narrative forms can address the experience of relating to our own stories and feelings in a constantly shifting urban space? How is the assertion of place meaningful in the face of GIS’s blank spatiality, or in the face of multinational corporatization that makes all spaces look and feel the same? And how, exactly, might a place acquire an aura of authenticity in such a context? But also, how does urbanization exist in the past; what are the visual forms of its memory? And what to do of all those dreamt-up presents that never came, of all those possible futures that never happened? Pipelines is an attempt to tell new city stories for our twenty-first-century reality.

— Daniel Laforest & Heather Zwicker

—————-

[1]This distinction is hinted at by Edward S. Casey in his 1997 book The Fate of Place. But it is most clearly made by Augustin Berque in his 2000 book Écoumène. Casey, Edward S., The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. Berque, Augustin, Écoumène. Introduction à l’étude des milieux humains, Paris: Belin, 2000). See also Lippard, Lucy, The Lure of the Local. Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society, New York: New Press, 1997.

[2] www.hitotoki.org. The “classic” view best demonstrates what we signal here.

[3] Saskia Sassen expresses it best when developing her well-known concept of the global city: “Today, there is no longer a simple straightforward relation between centrality and such geographic entities as the downtown and the central business district.” ( Sassen, Saskia, “The Global City: Introducing a Concept and its History”, in Mutations, Bordeaux: ACTAR arc en rêve centre d’architecture, 2001, p. 110).

[4]On circulation particularly, see Boutros, Alexandra & Will Straw (eds.), Circulation and the City: Essays on Urban Culture, Montreal / Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010.

[5] See Zwicker, Heather, Edmonton on Location: River City Chronicles, Edmonton: New West Press, 2005.