— DIAGONALS FOR A STRAIGHT WORLD —

Description

The current importance of suburban spaces as a common social problem offers a mixture of focus and disengagement. The focus is on how capital’s logic of speculation comes to be brutally inscribed into the land. The disengagement has to do with how no one really knows how to think of history when it comes to that particular space, and to the forms of life thereof.

The project aims to address this by positing that suburbia is arguably the sole sector of urban space with which we engage only horizontally. Moreover, it is the physical layout of suburbia that produces this horizontality. There exist a distinctly suburban field of view in North-America that possesses a political dimension because of that.

The little-encompassing eye of bourgeois utopia

1) The zoning regulations, stating that even commercial stretches will not have buildings with more elevation than x or y, are producing horizontality on a formal level.

2) The real estate speculative development of the neoliberal city, being at once devoid of roots and teleology (unlike the “planned city” of the past century), is producing horizontality on an communal level (the widely accepted word for this being “sprawl”).

3) The markers that the pedestrian and car-bound commuter will use for everyday orientation are rarely associated with landmarks visible because of their height. In a city like Edmonton, people are invariably going from crossroads to crossroads to find their way. This is thus producing horizontality on an individual level.

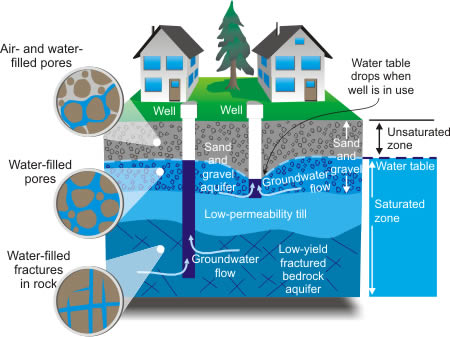

And in a soil-oriented economy like Alberta, it is a well know albeit rarely discussed fact that private land and home ownership are themselves horizontal processes

What happens underground stays underground

The individual does not own the resources potentially lying under the bedrock of his yard. Nor does he have access to the material remnants of memories it may contain. Verticality, from all accounts, seems to begin where the frontiers of property are becoming blurred.

Site of proposed housing development (Poltergeist, Tobe Hooper, 1982)

However, the commonplace assumption that the only ways to exist in suburbia are either to be lost or depoliticized does not take into account the verticality of the personal urban experience. There is a field of perception that ranges from the upward-tilted angle of the rooftops and beyond, as well as to the cluttered world of material traces and half-glimpsed, half-buried object on the ground below.

The new, new world

Engaging with this other potential world from the standpoint of 1) the affects, and 2) narrativity produces commonality in two ways. If suburbia can be defined by its high degree of homogeneity, then its emotional regime is even more prone to involve everyone. There are, potentially, a vast number of shared suburban experiences, however limited or even poor they might be. But one obvious problem is that this potential commonality is cut short by the segregationist layout of private land ownership and accessibility. No one really looks into each other’s yard. Curiosity in suburbia is not a producer of social relations and intersected stories; it rather destroys them through the specter of legality.

And yet that might not be the case when we look to the skies, or to the ground. The potential paths and narratives laying dormant above and under the functional angle of our everyday gaze are unhindered by fences, garages, and noise walls. How to re-produce their interconnections? There is an unexplored and as-yet unorganized emotional space on the edges of our peripheral vision where the notion of urban property loses some of its clarity. When we reconstruct the suburban experience by leaving out the visible field that corresponds to the functional economy of the everyday, what’s left? Can we attempt to make a world out of it? What form of realism will this produce? Will the results make us think of proximity and neighborhood differently within the neoliberal city?

A storyteller’s dream-space

Method

Creating and connecting individual stories (fiction or non-fiction) of suburban living spaces on one common digital map, using for a starting point 1) real artifacts that are scattered and half-buried in the ground 2) images only captured at a certain upward-tilted angle.

— User-provided photographies of the objects will be used and linked to the map in accordance with their location.

— Likewise, user-provided photographies of the skylines (or google-street view screen-captures, since they allow 290º vertical angle) will be linked to the map in accordance with their location.

— Essays/fiction narratives will be linked to to each photo location. Narratives will use the photos of objects/skyline as a starting point. They will possibly include other images, references, links, etc.

— Found objects and skylines can be connected together in accordance with a single location. But this is not a necessity.

— Stories can focus on one location, or they can connect two or more of them.

Scope

This project can potentially be opened to any number of individual. But it can also be restricted to workgroups in creative writing for example, or can be used in classroom context, or for critical research purposes. The nondescript nature of suburban spaces makes the project malleable in such a way that its initial implementation in Edmonton can be followed by other experiences in different cities, leading the way for comparisons and a better understanding of individual and communal living in today’s urban North-America.

Platform

Google-map/satellite/street-view

Authorship

Daniel Laforest — with the collaboration of Ryan Beauvais, Erika Luckert, and Joyce Yu.